The Evening

Graphic's

Tabloid

Reality

By Bob

Stepno

(written back when I was just a...)

PhD Candidate, UNC-Chapel Hill

School of Journalism and Mass Communication

Seventy years before the current debates

about television news sacrificing journalistic values to be

a form of entertainment,

or arguments about the sensational

excesses of

"tabloid television," there was a similar uproar about

the ethics and

values of newspapers, especially the three New York City

tabloids, the

Daily News, the Mirror, and the

Evening Graphic. The Graphic was the one the

other

two held up as a

bad example, calling it the "Porno Graphic" for its

emphasis on sex,

gossip and crime news. It only lived for eight years, but it

launched the careers

of Walter Winchell, Ed Sullivan, and others who went on to more

respectable

newspapers or abandoned reality (or at least New York) for

Hollywood.

or arguments about the sensational

excesses of

"tabloid television," there was a similar uproar about

the ethics and

values of newspapers, especially the three New York City

tabloids, the

Daily News, the Mirror, and the

Evening Graphic. The Graphic was the one the

other

two held up as a

bad example, calling it the "Porno Graphic" for its

emphasis on sex,

gossip and crime news. It only lived for eight years, but it

launched the careers

of Walter Winchell, Ed Sullivan, and others who went on to more

respectable

newspapers or abandoned reality (or at least New York) for

Hollywood.

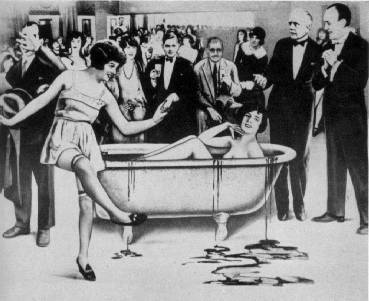

The

Graphic did things with photographs that respectable newspapers

wouldn't think of

doing... or at least they rarely would think of doing them after the

sex and

sensation-minded Graphic did them first. The

Graphic staged dramatic

"news" scenes in a studio for its daily multi-panel

"Graphic Photo Drama

from Life" feature, and to illustrate "True Story" style

first-person

stories. Bernarr MacFadden, publisher of the Graphic also

founded True Story

and Physical Culture magazines, both pioneers in photo

illustration in their

own way. The Graphic ran MacFadden's health advice, posed

chorus girls in a comic strip of "physical culture"

exercise demonstrations

(with joke captions), and reflected MacFadden's liberal attitudes

toward sex

and the human body. But it was most famous (or infamous) for its

composographs -- often startling

front page images created in the art department by cutting and

pasting the

faces of celebrities onto the bodies of often

scantily-clad

models posed to illustrate

some real-life scene where a camera simply couldn't go

(especially with the flash powder

cameramen used in those days)... into someone's bedroom, to

bathtub-ringside at a

wild Broadway party, to a hanging, into a closed courtroom at a

steamy divorce trial, into a

hospital operating room or beyond the grave...

scantily-clad

models posed to illustrate

some real-life scene where a camera simply couldn't go

(especially with the flash powder

cameramen used in those days)... into someone's bedroom, to

bathtub-ringside at a

wild Broadway party, to a hanging, into a closed courtroom at a

steamy divorce trial, into a

hospital operating room or beyond the grave...

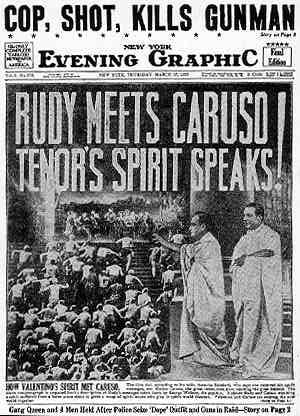

The caption says the image was prepared from a description by a psychic at a seance. The other page-one news of the day was "Gang Queen and 4 Men Held After Police Seize 'Dope' Outfit and Guns in Raid" and "Cop, Shot, Kills Gunman." The Valentino and Caruso image was included as the frontispiece of Silas Bent's 1927 book Ballyhoo, which concerns the rise of entertainment newspapers, celebrity journalism, public relations and commercialism in the 1920s.

Incidentally, note that the Valentino-Caruso front page is the final edition of that night's paper, marked with five stars in the top right corner of the nameplate. The Academy Award winning film Five Star Final was based on a play written by the Graphic's second managing editor, about a tabloid with a sensational murder story on its hands. Edward G. Robinson played the editor, and Boris Karloff was the star reporter! The film Blessed Event is based on another play -- about Walter Winchell's invention of the modern gossip column while he was at the Graphic. The paper's original managing editor, Emile Gauvreau, wrote two novels about his experiences, Scandal Monger (about the star gossip columnist) and Hot News (which also was made into an harder-to-find film), in which he makes his editor's enthusiasm for composographs sound like a mad addiction.

Composographs and coverage of Valentino are

probably

best described in Frank Mallen's 1954 book, Sauce for the

Gander,

which provided the other images on this page. Mallen was photo

editor

at the time, and felt the composographs of Valentino's funeral

were the best.

He emphasizes that the composographs weren't attempts to deceive

the public,

but to catch their attention with the "news" of

something

that couldn't be pictured any other way. (Most of the images on this

Web page are from that book, where they are credited "courtesy of Harry

Grogin," the assistant art director who apparently did most

of the creative work with composites at the Graphic. If anyone

knows

whether Grogin's collection survives in a museum or family

collection, I'd love to hear about it.)

Composographs and coverage of Valentino are

probably

best described in Frank Mallen's 1954 book, Sauce for the

Gander,

which provided the other images on this page. Mallen was photo

editor

at the time, and felt the composographs of Valentino's funeral

were the best.

He emphasizes that the composographs weren't attempts to deceive

the public,

but to catch their attention with the "news" of

something

that couldn't be pictured any other way. (Most of the images on this

Web page are from that book, where they are credited "courtesy of Harry

Grogin," the assistant art director who apparently did most

of the creative work with composites at the Graphic. If anyone

knows

whether Grogin's collection survives in a museum or family

collection, I'd love to hear about it.)

Perhaps the Graphic came along before the public was set in the habit of believing that photographs represented "the truth," at least as set as audiences became with the rise of high-quality photojournalism in the 1930s, including LIFE and LOOK magazines, wirephotos, candid 35mm photographs, and the courageous work of World War II photojournalists. But the trustworthiness of photos is something we've come to doubt in today's age of easy photo manipulation with computers and Photoshop. In advertising and entertainment, the camera is clearly accepted as a tool for creative illustration, not just for "capturing" reality. Do readers recognize the difference? Did the Graphic? Its arguable whether the Graphic was interested in capturing reality at all -- it was willing to create text stories out of rumors as well as turn hearsay into photographs. It had ghostwriters compose "first-person" diaries for publicity-hungry subjects, and it made news with its own crusades and stunts. Sometimes the boundaries between reality, story and stunt became blurred.

It's interesting to play "what

if." What if

other papers (with a tighter grasp on responsible journalism) had

adopted the Graphic's idea of creating photo

illustrations in the studio or darkroom? We might have a

different attitude

toward photography today, a time when photojournalists are

struggling with "image

ethics" issues filtered and sharpened by new technology.

That kind of speculation is hard to test as a theory. One

approach is to look at the reaction to the Graphic.

But back in the 1920s the greatest uproar wasn't about the

Graphic's manipulation of images, or even of people,

but about its habit of putting nudity and bedroom scenes on the

front page in a series of sensational

divorce stories.

That kind of speculation is hard to test as a theory. One

approach is to look at the reaction to the Graphic.

But back in the 1920s the greatest uproar wasn't about the

Graphic's manipulation of images, or even of people,

but about its habit of putting nudity and bedroom scenes on the

front page in a series of sensational

divorce stories.

That's the conclusion I came to after a few months of reading microfilm of the Graphic, the trade magazine Editor & Publisher, and critiques of the Graphic in magazine and newspaper articles from the 1920s. The details are in my paper titled, Staged, faked and mostly naked: Photographic innovations at the Evening Graphic, 1924-1932, which was well-received by reviewers for both the Western Journalism Historians Conference in Berkeley and (a slightly revised version) the 1997 Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication conference in Chicago, where it was chosen top paper in the Visual Communications division.

In printed form the conference paper was 29 pages long with 68 footnotes, something the Graphic definitely didn't have. I also prepared a version of the paper as a "page" on the Web, with all of the pictures and footnotes linked bidirectionally, so that you could browse the pictures or notes and jump to the right place in the text. (After all, the Graphic was for people who look at the pictures first. Perhaps I should write another paper about tabloids as "user interface design"?) I do want to experiment more with this business of presenting the same information in an online version with hypertext links while preserving the full linear version of the original. However, I also plan to turn the original conference paper into a journal article and have been advised by an editor to hold off "Web publication" until after the print version. In fact, that's how this Web page came about--as a less-academic essay that I could publish myself.

I hope to resume my research on the creators of the Graphic and their ideas of news, entertainment and ethics, maybe even work that into one Web with my dissertation work on online "news" and "entertainment" publishing. If you are doing related research or if you have more information about the Graphic and its creators, drop me a line by email to bob@ {my last name}.com.